There has been a certain morbid fascination with doomsday stories and end-of-the-world style flicks since the beginning of entertainment, dating as far back as H. G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds” and Mary Shelley’s “The Last Man.” It has continued up to the present day, with series like “The Walking Dead” and “The Last of Us” topping the proverbial charts. One of the best eras for apocalyptic media was, in my opinion, the 1980s, which saw a number of near-nuclear-miss films, among them John Badham’s “WarGames” and the “MadMax” franchise.

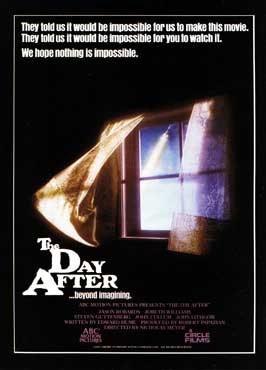

Grown from rising tensions and Cold War hysteria, Nicholas Meyer’s 1983 film “The Day After” is a speculative biopic about a fictional nuclear war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact and is perhaps, the best disaster flick from that decade.

“The Day After” follows a number of different people and their lives leading up to, during, and after the war. One of them, Russell Oakes (played by Jason Robards) is a doctor who lives with his wife in Kansas City and is preparing for his daughter’s upcoming move to Boston; on the Dahlberg farm outside the city, eldest daughter Denise (Lori Lethin) prepares for her upcoming wedding. A number of other minor characters engaged in their own lives help add a sense of depth to the world as the United States and the Soviets descend into war over Germany; all of these pre-war worries disappear in a heartbeat when warheads strike across the country, destroying Kansas City and the hundreds of missile silos throughout the region. Other characters include Airman Billy McCoy, a missileer eventually made sick with radiation, played by William Allen Young; and pre-med student Stephen Klein, played by Steve Guttenberg, who ends up seeking shelter in the Dahlberg’s bomb shelter.

What follows is a gut-wrenching ballad of loss, death, and suffering, compounded with the spread of rampant disease and the collapse of functioning infrastructure. Robards’s performance as a battle-weary Oakes, one of the only physicians at an underequipped, understaffed university hospital that wounds up bombarded with the sick and injured, is a fascinating portrayal of how our society would react in the face of genuine crisis; the gradual eroding of stable order as Oakes and his colleagues work themselves to near-death is haunting. Lethin’s portrayal of Denise’s descent from a hearty, lovestruck teenager to a woman lost in isolation-induced delirium after being trapped in a bomb shelter with her family for weeks on end is unsettling, if not disturbing.

The impact it had on the social environment of the day was profound. Over a hundred million people saw it during its initial broadcast on ABC’s prime-time network; then-president Ronald Reagan, who was, at the time, renowned for antagonizing the Soviet Union, reportedly changed his stance from being completely dead set against any form of Communism to one of belligerent coexistence. A pre-screening, shown to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had a similar effect. It was shown on Soviet screens in 1987, and, coincidentally or not, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed by Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev not long after. The treaty would eventually help lead to the end of the Cold War.

Considering such a gritty, grisly film can have that deep of an impact on global affairs, it’s no wonder ABC and local television affiliates opened live hotlines with counselors standing by. “The Day After” is arguably one of the most influential films ever made by an American studio, and even now, almost fifty years later, that influence is just as potent.

Altogether, “The Day After” is not just a thrilling watch; it’s a piece of film history.