From the Catastrophe to the Contentedness

Photo K. Corwin

Valerie Valcin (’16) was just a child when disaster struck her home nation of Haiti. Years later, she still deals with pain after the bone in her leg was crushed in the quake.

March 28, 2016

Disaster struck the small island nation of Haiti in early 2010. A magnitude 7.0 earthquake, followed by aftershocks and tsunamis, devastated the entire population. Less than a minute of trembling destroyed years worth of infrastructure and technological advancements. People were displaced from their homes, schools were demolished, and a state of destitution hung like a cloud over the land.

In the United States, many relief and awareness programs were instated in reaction to these events. Television specials like “Hope For Haiti Now” were sponsored by critically acclaimed celebrities like U2 frontman Bono. People around the nation became dedicated to helping alleviate the problems, but fortunately, few people experienced these events as intensely as Valerie Valcin (’16). Valcin was born and raised in Haiti and lived there when the earthquake occurred.

“[As the earthquake occurred, it was] shocking, because no one knew at that moment what was going on,” Valcin said. “We thought the world was going to end. It was shocking then and it’s still shocking now, actually.”

During the quake, Valcin was at home. She and her family lived in a house on a hill and when the tremors started, she ran outside in an effort to save her younger sister, now sixteen, who was playing in the yard. While she was outside, a big building nearby began to crumble. Everything happened quickly.

“When the top of the building fell, my mom grabbed me and pushed me back, but I fell in panic,” she said. “I couldn’t move and my leg just like [claps hands to mimic leg] went flat onto the ground.”

Valcin’s leg was trapped under the debris. The bone was incredibly crushed, so she underwent a surgery to relocate part of her ribs to her leg, then received skin graft treatments. Without hesitation, she said that these surgeries were the worst part.

“Some days they were like, ‘We’re going into surgery, no eating,'” Valcin said. “And then they’d say, “‘Okay… we’re not going to do it today, but still don’t eat because we’re going to do it tomorrow.’ We spent most days not eating.”

Immediately after the earthquake, Valcin and her father moved to the States, with her first experience in the US being in a hospital. Although she found the moving process both frightening and painful, she recalls her days in the hospital with reverence.

“I met some people that barely knew me, that just knew my story, and without a doubt, they took care of me and helped me in any way possible.”

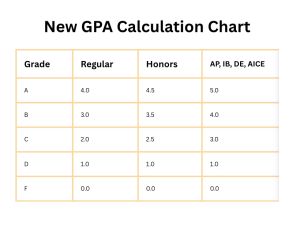

Once assimilated into American culture, Valcin was struck by our school system. In Haiti, to get a good education, one has to pay for everything, from uniforms to tuition. To Valcin, it was impressive that children in the US here can receive quality education without paying hefty fees.

Her own experience at school, however, has not been quite as impressive. Because of her unusual walk, Valcin has faced problems with bullies.

“Since middle school, people have been talking about the way I walk, but they don’t know what happened, why I walk like this.” Valcin said. “I limp a little because my left leg is not the same length as my right leg. That’s why the doctors say I need surgery. People always say, “Oh my God, why is she walking like that? What’s up with her?’ I was bullied for this in middle school. I was like, “I just walk like that. It’s just surgeries, it’s not my fault.'”

For Valcin, high school has been a nice change. Though she still has to endure surgeries whenever she has time off school, she enjoys life right now: reading, watching television, going to the movies with her friends.

While she still carries around the remnants of the earthquake, her limp has taught her the importance of accepting other’s differences.

“Some people bash me for how I walk or how I do things. But I think that before you judge someone, you should just ask them questions,” she said. “Before you judge someone, you need to talk a walk in their shoes.”