Arooj Aftab’s Vulture Prince- a mesmerising labyrinth of dusk and dream

Pakistani composer Arooj Aftab returns after three years with a new seven-track LP

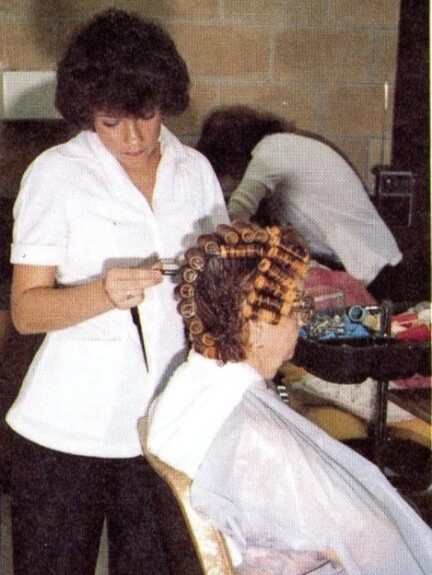

Photo Vishesh Sharma

The album cover for Arooj Aftab’s “Vulture Prince”.

May 21, 2021

Arooj Aftab, Pakistani composer, vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, released her latest record, Vulture Prince some weeks back. Garnering similar critical praise, yet more apparent popularity, than her two prior albums, 2015’s Bird Under Water and 2018’s Siren Islands.

Going into this, I knew nothing. Like, literally nothing. A friend mentioned it to me in passing and I bookmarked it on my phone because I knew a smidge of Hindustani music. I, however, did not know any Ghazal, nor much about Arabic music in general, nor any understanding of Urdu, the language in which the album is sung. So set’s.

For a long time, I’ve been looking for a modern analog to the poetic expressionism and long-form, dreamy songs of the chamber-folk singer/songwriter albums of the 1960s, such as Tim Buckley’s Happy Sad or Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. That kind of music takes a lot of emotion, ability, and wonder, to write. It allows for the listener to float in and out, exploring the sounds as both a pleasant atmosphere and deeply heartfelt listening in tandem. Anyway, I feel like I’ve found that, at least in spirit, with this record.

Vulture Prince is an album highly open to description, yet above exact classification. So much could be said about this music that you could fill an entire page with adjectives, and yet not fully convey everything it has to offer. A perfect way to start would be with its cover; hazy and dusky, but melancholic and deeply mesmerizing. The atmosphere is so critical here that there’s even been a perfume oil produced to accompany the album. Its description states: “Wet earth, ripe stone fruit and a faint smokiness tell a story about the color purple and all its beautiful scents amplified by monsoon season”. Again, just as accurate a description to the music itself.

To actually talk about the music, the first track, “Baghon Main” opens you to the world. A picked instrument, harp-like, leads in; slowly, gracefully, the listener is swept away into a dreamy, dark, yet pastoral soundscape. The first thing many listeners will take note of is her voice; at times smooth and delicate, at times human and conversational, similar to bossa nova artist Nara Leão’s in the way she floats over wavelike guitar lines and subtle flutters of strings like a brisk wind blowing over a shoreline.

The instrumentation is a key point of favor for the album as well. While rooted in traditional sounds with a string and harp backing, Aftab’s compositions come to light with a variety of nontraditional instruments, such as guitar, flugelhorn, and even synthesizers. A modern, unique production style helps to add even more depth— elements are sparsely treated or reversed in a way not immediately apparent upon first listen, but providing a subtle sense of disorientation for the listener.

Also, while relatively unimportant to mention, the mixing on this—courtesy of Grammy nominee Joshua Valleau—is phenomenal: the soundstage is at once vacuous and intimate, with really subtle reverb. A great balance of clarity and purposeful obscurity.

The final thing I’d like to point out about this record is Aftab’s compositional style. In their entirety, the works are somewhat free-flowing and sparse; yet each instrument has its place and fits it well. However, this amounts to some rather long-form songs, which, while effective in the chamber pieces, namely tracks 2, 3, and 7, can lead to a bit of dragging on the more poppy cuts, like the dub-driven “Last Night”. Nonetheless, a sense of compositional competence is portrayed, and at times reminds me of Simon Jeffes’s works.

Overall, Arooj Aftab’s Vulture Prince is rightfully worth the high praise its been given by NPR and contemporaries, and will definitely show up on a lot of year-end lists for 2021. But not only that— it shows that the spirit of the poetic, heartfelt chamber music of old is still alive and well in the modern era, with quite a few new twists to play around with as well.

Mark • May 30, 2021 at 8:55 am

Well done Samuel.

Never thought I’d be checking out Urdhu chamber music but here we are.